The PDP-1. I've read about this computer many, many times in a number of seminal books and publications: Hackers, The Ultimate History of Video Games, The Soul of a New Machine and Rolling Stone to name a few. I've seen pictures of it, I've stared at images of the teletype but I've never ever been even remotely close to one. Here it was, here was the machine that allowed old-school hackers like Stephen "Slug" Russell to create the games of their dreams, the fantasies that had remained bottled in their heads. And it was right in front of me. Sure it wasn't actually operational, and Spacewar was running on a Vectrex slightly to the left instead of its home machine, but it was close enough to touch.

My mouth just started yammering about the PDP-1 to unitdaisy, who was making this trek with me. Stacks of information, everything I had read about this fabled computer started pouring out of my mouth, much more information about it than she surely ever wanted to know but my mouth was desperately trying to compensate for the dissonance going on between my eyes and my brain. Yes, I was seeing was a PDP-1 right before my very eyes, not just an image on another printed page..

The high point of Game On and we had just walked through the door.

Game On is a world-wide travelling exhibit, allowing visitors to get their hands on over 100 video games that showcase the artistic and technical evolution of the videogame industry, as well as its influence on popular culture. This is not the first exhibit of its kind (I believe Videotopia holds that honor, especially if you're looking solely at arcade games) but it certainly seems to be the most successful, especially since before its trip to the United States Game On was supposed to become a permanent museum installation. Instead, the exhibit has crossed the Atlantic to Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry to tantalize those who weren't able to make the trip out to London or Edinburgh prior.

That's a long trip for a PDP-1 to make. It's a lot of mileage for all of those arcade cabinets, consoles, games, controllers, peripherals, design documents, and handhelds to accumulate. It's also a lot for visitors to sort through, but oddly enough the exhibit feels almost small in its scope, like each enclosed space is barely paying lip service to the room's theme. The entry section that housed the PDP-1 was the arcade portion of the exhibit and contained sundry early arcade machines, including an original Pong cabinet and two Computer Space games. Sadly, neither the Pong or Computer Space machines were actually playable but their presence made all the difference. These classics were placed next to a projected MAME cabinet, a Space Invaders tabletop, and a few other more common arcade games. Conspicuously absent were any pinball machines, especially odd since Chicago was the home of the Bally Manufacturing Company (now Bally Gaming), widely considered the company that pioneered the coin-operated machine industry.

The MAME cabinet is indicative of Game On's stance towards emulation, namely that they can't get enough of it. If a game to be displayed could be presented in an emulated form, they opted for that over the original platform. While I understand that they can't allow the unwashed masses to paw some of the more delicate older consoles and machines, I find it inconceivable that they would opt to use the Gamecube port of Ocarina of Time over the Nintendo 64 version. Surely they could have paid a 14 year old a pittance for a used Nintendo 64 and a copy of Ocarina of Time rather than just using the bonus disc that came with their pre-ordered copy of Wind Waker. The fact that the plaque notes Ocarina of Time not as a Nintendo 64 game, but as a Gamecube property does nothing but add insult to injury.

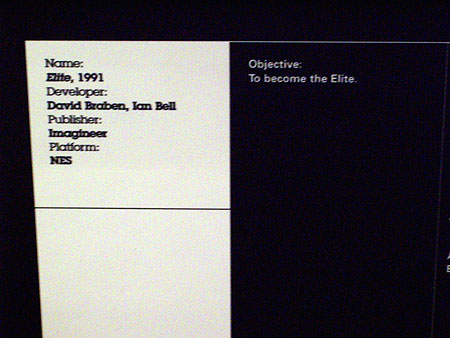

There were similar erroneously labelled stations situated throughout the exhibit. One booth said it was showing Parappa the Rappa, released on 2002 for the Playstation 2. Obviously they meant Parappa the Rappa 2. If you were looking to play Creatures for the Playstation well, I hope you enjoy Animal Crossing! However, in general the console section of Game On was competent, including a number of seminal games such as Elite, R-Types and Project Gotham Racing 2. Or not. Some of the console game selections had me scratching my head, especially the inclusion of 1080 Snowboarding and OutRun2. Not to knock any of these games (especially OutRun2 which I rather liked) but to put them in on display in a museum really doesn't do the surrounding games justice.

By the time I left the console room, the slight buzz leftover from the excitement of the PDP-1 hadn't quite been rubbed out yet, but the the upcoming 'game development' section would see to that. Between the wall of Golden Tee machines and Dragon's Lair storyboards my heart shriveled a bit in my chest. I pondered why all three Golden Tee machines were placed behind glass, mused over the 'How to make a tree for Golden Tee' poster and was left nonplussed by the Golden Tee preliminary cabinet sketches. While I understand that Golden Tee is the greatest contribution the fine city of Chicago has made to the world of video games in years, 'How to create a tree' doesn't show any tangible insight into the game design process nor showcase any of the appeal of the game. There have been thousands of golf games before Golden Tee, so show us what sets Golden Tee apart from the pack! Sadly, this was slightly more informative than the second part of the 'development' section. Personally, I would label a collection of storyboards and art pieces of Dragon's Lair an exhibit on how to develop an animated feature, not a video game.

It was all downhill from there. Subsequent sections of the exhibit dealt with poor generalizations of gaming in the U.S. & Europe, and Japan. The Western portion contained an assortment of sport games (and Burnout 3) wedged up against the only real item of interest: Poly Play. Poly Play was a communist arcade game manufactured in the late 1980s in East Germany to satiate the public's interest in gaming, and keep them away from the capitalistic coin-operated arcade games. The machine looked like it was poorly cobbled together out of spare television and alarm clock parts; in fact the entire cabinet looked like it was manufacted during the 70s as a 14 year old's afterschool project. Unfortunately we were unable to see if the quality of the games matched the shoddy appearance of the hardware, as the monitor simply displayed a blue screen. Regardless, this reminder of forgotten ideologues was a welcome change from the sea of American and European sports games.

I turned the corner and was welcomed by an audacious pachinko display. There's no pinball to be had, no Bally machines but there were two garish, unplayable pachinko machines to tout the Japanese gaming experience? A large sign loomed over this space: "JAPAN - How do games reflect the culture in which they are made?". Right underneath it lay an ornate display consisting of bubbly hearts framing a television showcasing the dating simulation Tokemeki Memorial. I think I get the message. Just in case I didn't, the message was spelled out on the supplemental plaque! The rest of the Japanese section was peppered with novelty peripheral games including the ever-industrious Dance Dance Revolutionand the weighty & intimidating cockpit of Steel Battalion, both of which stood by the train simulation game Go By Train (Densha de Go) and a Sailor Moon game. Overall, the exhibit felt more like parody than an attempt at being informative.

Right around the corner lay a treasure-trove of handhelds, including a TurboExpress that had me salivating. However, this section was also apparently part of the 'kids' gaming showcase and had a pack of hyper children gripping and grabbing the several GameBoy Advance SPs laying out in the open. Most of the intriguing handhelds were trapped in a glass bubble that I yearned to free them from. I've never had an opportunity to spend a few minutes with a WonderSwan for instance, and apparently I never will.

The next room extolls the virtues of multiplayer gaming design, but while walking through I'm struck with the following musing: they probably could have come up with better examples of multiplayer games than a large Bomberman match and system linked OutRun2. And you certainly would think that they would have higher quality games representing Chicago as opposed to Powerball Billards and Spongebob Squarepants 3D Obstacle Odyssey. Luckily, my dissatisfaction with Chicago's representation was distracted by the flashy Discs of Tron cabinet and solid design of Maneater.

Luckily the music portion of the exhibit didn't disappoint. In fact, I was partially enthralled by the opportunity to play WORDIMAGESOUNDPLAY, the TOMATO designed game from the UK released only in Japan. Of course I quickly realized why after about five minutes with it - the game is shallow and lacking any sort of challenge or depth. Although, if you wanted to take a break from the brilliance of Rez or savvy of Space Channel 5 (the program says it was Part 2, but the disc was playing the first game) you always had the option of listening to a variety of gaming soundtracks. Of course one of the monitor stations was broken but hey, this is a museum and not a Borders, right?

Game On ended with a whimper, its final exhibits being mere footnotes of gaming past as opposed to examining the looming spectre of gaming future. A few scrawled modern character sketches of Mario and Sonic coupled with Super Mario All-Stars and an emulated Sonic 2 stood parallel to a display espousing the wonders of the ESRB. The bitter taste growing in my mouth was only amplified by the slim retrospective of gaming magazines and a lone table containing the following wonder.

The PDP-1 was a distant memory in my mind by then, buried by the numerous slight misnomers and aberrations in the exhibit, compounded only by our reactions to the gift shop. As we checked the museum's wares for more information on Game On and gaming in general, we found nothing but a meager display, mostly hocking cheap 10-in-1 retro tv tchotchkes and shirts that pale to the original exhibit's design sensibility. While Game On does provide for the opportunity to get your hands on a multitude of classic games, the circumstances aren't nearly what one would hope for them to be. The few gems wedged between the emulation, incorrect data and non-functional units do not have enough power to transcend the exhibit, and the information that was there wasn't nearly enough to provoke any thought about the evolution of gaming, much less cultural contributions that video games have made. Perhaps this is just another case of nostalgic whiplash, where the history should be read, contemplated and idealized rather than recreated. In that case, skip the exhibit and pick up the studiously insightful Game On book, which compensates for many of the exhibit's inadequacies and will pique your mind much more than the hands-on installation is capable of.

#1 Stilgar Mar 10, 2005 07:50pm

Thats like your ultimate drunksaling experience. Minus the booze (though possibly not) and buying the neat things you see.

#2 R. LeFeuvre Mar 10, 2005 09:39pm

Don't think he wouldn't have had it been an option!

Who wouldn't want to own a PDP-1?